History of the University Library – from manuscripts to e-books

History of the University Library – from manuscripts to e-books

With a history reaching back half a millennium, the University Library is as old as LMU itself. What started out as a collection of textbooks has become not only one of the largest libraries in Germany, but also a place for studying, communicating, and hosting events.

The subject libraries of the University Library are popular places to study, and students are particularly fond of the learning centers: “This one looks so modern,” enthuses communications student Mia. “It’s nice and bright and the beanbags create a feel-good vibe as soon as you walk in.”

Beanbags and feel-good vibe?

For a student at the early incarnation of LMU, the Hohe Schule zu Ingolstadt, these words would have been baffling. Just as the concept of the septem artes liberales, or seven liberal arts, would be alien to today’s cohorts. These subjects were taught in the faculty of arts at the Hohe Schule and a 15th century student had to learn them more or less by heart – in Latin, it goes without saying. Only then could he – women were not yet admitted to the university – continue his studies at one of the three higher faculties of theology, jurisprudence, or medicine.

Educational books were very expensive in those days. So that less affluent students could keep up with the courses at the Hohe Schule, the most important volumes were compiled in a sort of textbook collection – the nucleus of today’s University Library with its holdings of more than five million volumes.

How a subject library works: The Philologicum

“A highly sought-after place to learn”

Film: Benjamin Asher/LMU

Books on a chain

“The collection was gradually expanded, and by the end of the 15th and start of the 16th century, the first catalogs had been produced,” says Dr. Sven Kuttner, Head of the Special Collections Department at the University Library. This valuable store of books was arranged as a so-called chained library. The scholars of the day found the relevant works systematically ordered, securely chained, and only available for consultation at the lecterns provided – borrowing them was not an option.

Lending is a standard service offered by the University Library today. Only the stock of old and rare books – many of them from the Hohe Schule – are not available for borrowing. These precious items are held apart in the Special Collections Department headed by Sven Kuttner. But this does not mean the old manuscripts, prints, and incunabula are entirely inaccessible, as scholars studying these historic works can consult them in the Special Collections reading room.

The same goes, incidentally, for the materials in the University Archive, which was incorporated into the University Library in July 2021. People can consult old student ID cards, say, or historical personal files, to learn something about the student days of their grandmother or grandfather. And researchers can fill in gaps in our knowledge about important historical personalities with connections to the university.

“Right next to the University Archive in Munich’s Freimann neighborhood, the University Library has a shelving facility. Thanks to the inter-library shuttle service which stops at this facility every day, people can also order historical documents from the LMU Administration,” explains Dr. Susanne Wanninger, Head of the University Archive Division. This spares people what can be a long trek to the archive, which is located in the northern outskirts of Munich not far from Freimann subway station.

Large parts of the old holdings have already been digitized and are available for download. In short, access to the library’s old stock is freely accessible; the library is a site of free academic pursuit without restrictions.

Special Collections Department at the University Library

Behind the hardest door in Munich

Film: Benjamin Asher/LMU

‘Armory’ of the Counterreformation

In the early 16th century, things were very different. At that time, the Hohe Schule was the nerve center of the Counterreformation. It was the workplace of the theologian Johann Eck, one of the doughtiest theological opponents of Martin Luther. Eck carried out disputations with Luther in Leipzig, and he traveled to Rome to help frame the Exsurge Domine papal bull censuring the Wittenberg reformer.

The university’s stance as a defender of the old faith had effects on the library, but not in the way one might expect. Rather than banning ‘heretical’ works from its holdings, it did the opposite: “There were many first prints of Reformation texts in the library,” says Sven Kuttner. “This was because the university was engaged, as it were, in professional enemy reconnaissance.”

And so the library held two copies of Luther’s ‘September Testament’ – his translation of the New Testament from Greek into early modern high German. One of these copies contained numerous handwritten annotations of Eck’s.

“There were many first prints of Reformation texts in the library. This was because the university was engaged, as it were, in professional enemy reconnaissance.”

Peter Canisius was a professor at the Hohe Schule. The Jesuit priest viewed the library as a sort of intellectual armory in the fight against the Protestant heresy. He urged the Catholic Church to have its own library, as otherwise its defenders would have to confront the enemy like “soldiers without weapons.”

The Jesuits would dominate the running of the university over the following decades. Over the course of the 16th and 17th centuries, they fundamentally reshaped the library of the faculty of arts, shifting the focus of the collection to theological and philosophical works. The members of the Society of Jesus systematically excluded all literature that ran counter to their religious convictions. Professors interested in secular topics lost access to important works, censorship reigned, and some books were even destroyed. Researchers who did not possess private libraries were effectively prevented from pursuing their work.

Gifts, acquisitions, and interlibrary loans

In the 16th century, the library also experienced a period of huge growth, primarily as a result of donations. For example, the Hohe Schule received the extensive collection of Johann Eglof von Knöringen, Prince-Bishop of Augsburg. In addition to paintings and objets d’art, this included numerous writings and books. Some of this literature came from the library of Erasmus of Rotterdam, and these works are kept today in the library’s Rare Books Division.

“We still get gifts and bequests today, but they don’t play a major role,” says Sven Kuttner. They mostly take the form of private libraries donated by professors. “Generally, the library already has copies of most of the books,” he notes. “So we concentrate primarily on the more valuable, rare books.” Although interlibrary loans still happen, this practice too is declining: “Most dissertations today are published electronically, so there’s no need for these exchanges anymore,” remarks Kuttner.

“Most dissertations today are published electronically, so there’s no need for interlibrary loans anymore.”

In Bavaria, moreover, legal deposit – that is, the requirement on publishing houses to submit a copy of every new publication to a repository – has been a statutory obligation since the 17th century. “Legal deposit played its greatest role in the 19th and 20th centuries, when the University Library was the mandated deposit library for the Upper Bavaria region,” says Sven Kuttner. In the 1970s, Munich was one of the leading publishing centers in the world after New York, he adds. And so the volume of books that statutorily entered the library’s holdings swelled accordingly, which of course required suitable logistics in the form of shelving facilities and transport options.

Special Collections Department at the University Library

“Sum Erasmi”: From the collection of Erasmus of Rotterdam

Film: Benjamin Asher/LMU

University and library move from fortress town to the banks of the Isar

Speaking of logistics: A heavy, iron-bound chest is kept to this day in the Special Collections Department of the University Library. Just one look at the rugged object tells you it can withstand wind, weather, and sundry other trials. The chest symbolizes the successful translocation of the university and its library from the mighty fortress town of Ingolstadt to Landshut an der Isar. This was a journey of some 80 kilometers, which could take several days to accomplish in around 1800.

Spiritual renewal through relocation

The move had been mooted for some time by reform-minded professors. In making their case, proponents highlighted the proximity of students to soldiers from the Ingolstadt garrison, which certainly was not always without its problems. But the primary reason was actually to bolster the shift away from Jesuit influence, which lingered in the intellectual superstructures of the Hohe Schule despite the abolition of the order in 1773, with a corresponding physical relocation.

When the fortress of Ingolstadt was menaced by Napoleonic troops in 1800, there was the more immediate and mundane argument of removing the Hohe Schule from the clutches of the French. Advocates for the move, with the support of the new Prince-Elector of Bavaria Maximilian IV Joseph, prevailed over the objections of professors and residents.

The University Library in Landshut: third largest in German-speaking world

Thirty four-horse carriages were available for the transport operation, which – organized in batches – took several weeks to complete. Each professor was responsible for their “own” stock of books, arranging for them to be ordered by bibliographic identifier, packed in sturdy chests, unpacked again on the second floor of the former Dominican monastery, and then sorted and shelved in their new home.

The professionalization of the University Library continued apace in this city on the River Isar, and its holdings were intensively cataloged. It also increased in size, not least due to the secularization of monasteries and their libraries in the years 1802 and 1803. Soon the University Library would contain some 120,000 volumes, making it the library with the third-largest holdings in the German-speaking world after Göttingen and Breslau.

Once highly restricted, today customer-focused

Use of the library is highly convenient nowadays. Lending and returning run like clockwork thanks to a sophisticated workflow. If the book you are looking for is not available in the open stacks, you can use the online public access catalog (OPAC) to order, collect, scan, and take out the work in question. Machines are often available for automatic book return. Special booths can be reserved for concentrated study or group work. Wireless internet is provided along with plenty of power outlets and earplug dispensers. You can even bring drinks into the reading room, provided they are in secure bottles that close properly. And for any questions, staff are on hand to assist.

Students were not allowed to borrow everything

Library use in the past was not quite as customer-focused as today. “Access to books used to be highly restricted,” explains Sven Kuttner. “There was one loans desk for professors and one for students, and the latter were not allowed to borrow everything.”

Moreover, users were expected to return books on time and handle them with care – or else! The librarian Maurus Harter in Landshut was known for his fierce indignation when books were returned late. One time, so the story goes, he actually grabbed a professor by the ears and shook him because the latter had fallen asleep in the reading room and torn a copperplate print! Mind you, Harter did at least apologize.

Irascible librarians aside, users were issued library tickets and the opening hours were from 9 to 12 in the morning and 2 to 5 in the afternoon. During winter, the library closed an hour earlier due to a lack of artificial light.

LMU and its library move upriver

In 1826, the interlude in Landshut came to an end. King Ludwig I of Bavaria wanted the state university to be located in “his” royal seat of Munich. So it was time to pack up the books again and send them onward. Fortunately, through the translocation of the university from Ingolstadt to Landshut, and through the transporting of books from the secularized monasteries, the staff had acquired some know-how in book logistics.

“Lack of space is a recurring theme throughout the history of the library“

Following a brief stopover in St. Michael’s Jesuit college on Neuhauser Strasse, the library was finally conveyed to the main building in Ludwigstrasse, which was completed in 1840. Its new home was on the third floor of the north wing, where the subject library for philosophy and theology is housed today.

Before long, the library was running out of room again. “Lack of space is a recurring theme throughout the history of the library,” says Sven Kuttner. This shortage became particularly acute in the period from the First World War to the 1920s. Books had to be placed in two rows, one in front of the other, to accommodate them all.

The reading room was like a miserable student kitchen

Georg Wolff, director of the library from 1920 to 1925, lamented the parlous state of the University Library, comparing the main reading room to a “miserable student kitchen” and the professors’ reading room to “the dingy smoking room-cum-lounge of a minor spa resort.”

Academic calefactory

Seemingly, it was only in the winter months that the reading room could provide feel-good vibes for students. Dubbed the “academic calefactory” after the warm room in monasteries, it was always packed when the weather outside was freezing. Library director Karl Emil von Schafhäutl wryly commented on this state of affairs in the mid-19th century: “There they sit, the sons of the alma mater, as if crammed into a sheep pen. Does Apollo lead them here, or just a lack of turf?”

The University Library also benefited in the short term from the extension of the Main Building in 1908/09 though the construction of the Bestelmeyer annex, which included the atrium and the Audimax lecture hall. This not only created the large northern shelving facility with capacity for over 150,000 volumes, but also gave students more space to study.

Technical innovations were introduced to improve the efficiency of the library. A striking example was the novel conveyor belt for the easier transport of books. Operated by hand crank, this contraption was prone to breaking down. Because it was encased and not freely accessible, moreover, mice were emboldened to make their home there.

Rising student numbers after the First World War further exacerbated the shortage of space. One of the ways in which the university tried to address this problem was by acquiring Kunsthaus Brakl. Located on Beethovenplatz in the medical quarter, this was the villa of opera singer and gallerist Franz Josef Brakl. Today, the building is home to a state-of-the-art reading room for medical students. Even after its renovation in 2012, it retains the elegance of the former house of culture.

Subject library Medizinische Lesehalle (Medical reading room)

A former artists’ residence as a library for medicine

Film: Benjamin Asher/LMU

Young students engage in book burning as “radical cure”

The tenth of May 1933 was a dark day for books and the culture they represent. On Munich’s Königsplatz, students from LMU and the Technical University eagerly tossed “un-German” books by Jewish and politically undesirable authors into the flames.

Radical cure with cheerful audacity and unburdened by librarian scruples

Director of the University Library, Adolf Hilsenbeck, praised the young students for carrying out “this radical cure with cheerful audacity and unburdened by librarian scruples.” This was a most troubling statement to issue from the head of one of the largest and most important university libraries.

However, the books by undesirable authors did not disappear from the library. Instead, Hilsenbeck ordered the ‘degenerate’ literature to be placed under the “strictest house arrest.” The works were locked away in Room 315, the so-called Remota collection. Stigmatized with the letter “R” or a red insert, they were now quarantined and practically no longer available to borrow or consult. Access was limited to academic researchers. The library still holds the books that were banished back then. Although they bear the historic marks of their branding, they are no longer locked away of course.

Hilsenbeck was in fact never a member of the Nazi Party, nor were most of his staff at the library. Even the appointment of staunch National Socialist Joachim Kirchner as successor to Hilsenbeck did not lead to significant politicization of the library’s operations. It would seem this was partly due to the new director’s background. Kirchner was a native of Berlin and was appointed to the office as a protégé of chief Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg. He understood little of the customs of Bavarian library work and committed all kinds of blunders. He was not much liked by his colleagues.

“Nevertheless, Kirchner managed to bring the most valuable of the library’s collections to safety when Munich was being bombed,” recounts Sven Kuttner. Despite these efforts, a third of the holdings were lost in 1944 when a bomb crashed right into the main building. Fortunately, it was possible to replace some of these books with copies from the many institute libraries.

New start with old concept

The rise of the decentralized academic departments known as “seminars” was a trend during the university’s period in Munich. In 1892, there were already 28 of these “seminars,” which maintained their own libraries. As Sven Kuttner explains: “After 1945, the bell tolled for these department libraries, the establishment of which was driven partly by the exercise of professorial power, in favor of the University Library.”

After 1945, the bell tolled for the department libraries

The University Library itself got a new building in the 1960s, which Sven Kuttner characterizes today as a cost-saving measure: “The library moved into the old “saltworks” building (Salinenbau) adjacent to the Gärtner building, preserving the façade of the redbrick structure.” This building was formerly the headquarters of the Bavarian mining and saltworks administration.

For Kuttner, this was “a doomed attempt to reanimate the moribund tripartite library design, with the stacks in the center, the administration around it like a circled wagon train, and the user area on the periphery” – a library concept from the 19th century without added value for users.

In other parts of West Germany, there had already been modular concepts based on free accessibility, which in fact had long been the standard design in the United States.

“It’s no wonder,” says Kuttner, “that the library life of students took place in the respective department libraries as places of exchange and concentrated studying.”

Department libraries fight the law

Under the provisions of the Higher Education Act of 1974, the decentralized structure of small department libraries was to finally become history in favor of a unitary LMU University Library. There was a lot of resistance at LMU to the change, and twice the university filed legal objections under the rectorate of Nikolaus Lobkowicz, because it feared bureaucratic excess. And twice it lost.

“The definitive enforcement ruling of 1980 determined that the entire holdings of the department libraries would be transferred to the University Library,” says Sven Kuttner. This led to the gradual construction of large subject libraries. Prominent examples include the library for psychology and educational sciences, which was established in the 1980s in the distinctive pink “Schweinchenbau” building on Leopoldstrasse, and the library in the English Garden.

“The library of today has to be pragmatic and fulfill modern demands.”

The last department library to be absorbed into the University Library was that of the Faculty of Law in 2022. It is housed today in the renovated “Book Tower” (Bücherturm) on Professor-Huber-Platz. If the enforcement ruling to abolish the department libraries outraged many professors at the time, a small library is almost unthinkable for the new generation of university lecturers.

“They’re no longer viable in large interdisciplinary research units,” says Kuttner emphatically. “Today’s library has to be pragmatic and fulfill modern demands.”

Subject library Chemistry and Pharmacy

Concentration with a click: Digital media in vogue

Film: Benjamin Asher/LMU

Print on the retreat

And naturally it should be electronic as well. “Today, everything revolves around the question as to whether a publication is available as an e-book.” That being said, notes the Head of Special Collections, the University Library was the first library in Germany to offer e-books at the turn of the millennium. This was followed by the creation of a publication server, because the demand for the electronic publication of dissertations kept growing.

“The various doctoral degrees had different regulations in this regard. Some of them still required a printed publication,” says Kuttner. The medical faculty broke this trend: “Print dissertations are effectively a thing of the past there.” The last bastion of the old Gutenberg world was the legal faculty. But even there, electronic publications are increasingly making inroads.

Borrow-to-go during the pandemic

Since 2020 at the latest, when the coronavirus pandemic led to the immediate closure of the university, digitality has been the order of the day. “There was no notice,” recalls Kuttner. “We had to shut down operations in short order.”

There was a run of students on the photocopiers and “we digitized works in shifts,” says Kuttner, who admits that “we stretched German copyright law to the limits with the indulgence of the publishers.” The numbers of people accessing electronic books shot up, while the borrowing of physical books pretty much collapsed: “After all, we weren’t allowed to open.”

Gradually, the University Library was able to resume operations again. This included improvised measures such as to-go counters at the library window. “When library historians get round to treating the coronavirus period one day, 2020 will definitely count as one of the great caesurae.”

Place of exchange instead of a book barracks

The physical book no longer necessarily plays the leading role in the University Library, which itself has long ceased to be the “book barracks” it was in the 1960s, in the words of Sven Kuttner. Its 14 subject libraries not only offer a large stock of printed and electronic media, but “today the University Library is a social meeting place, a venue for exchange, collective learning, and culture,” outlines Kuttner. This is what today’s students expect from a library, he observes. And the library takes these expectations seriously: Just recently, the “UniLounge” was inaugurated at Geschwister Scholl Square – a barrier-free learning center with some 100 workspaces situated in an historic vault.

“Today, the University Library is a social meeting place, a venue for exchange, collective learning, and culture.”

“We’re determined to expand the vital learning infrastructure for our students as enrollments increase,” emphasized Professor Oliver Jahraus, Vice President for Teaching and Studies at LMU, on the occasion of the official opening in November 2024.

Exhibitions in the Central Library

Treasures of the library in the spotlight

Film: Benjamin Asher/LMU

Showcasing history

For those interested in history, the University Library has a great deal to offer. And not just fascinating stories, but also many artifacts that are worth displaying, says Annika Assil, who is responsible for exhibitions in the Special Collections Department. Showcasing this history is another important part of what the University Library does.

“We offer guided tours – for example, during the Long Night of Museums in Munich. We think it’s important to show the University Library’s treasures to everyone who is interested,” affirms Assil. There are twelve display cabinets for this purpose in the main library, and temporary exhibitions are presented in subject libraries: on 550 years of history of the University Library, say, or the current exhibition on the development of German-Jewish cultural media for children in the 1920s and 1930s. Exhibitions can be visited during the opening hours of the libraries – or in the case of the main library, during the building opening hours. The morning hours before the issue desk opens, for example, are an ideal opportunity to enjoy the displays. And of course, exhibitions like the one marking the 550th anniversary of the library are additionally available online.

The exhibitions also feature items from the University Archive. “There are so many stories hidden in the archives,” says Susanne Wanninger. “It’d be wonderful if more people would delve into them and investigate all the fascinating topics to be discovered there relating to the university’s history.”

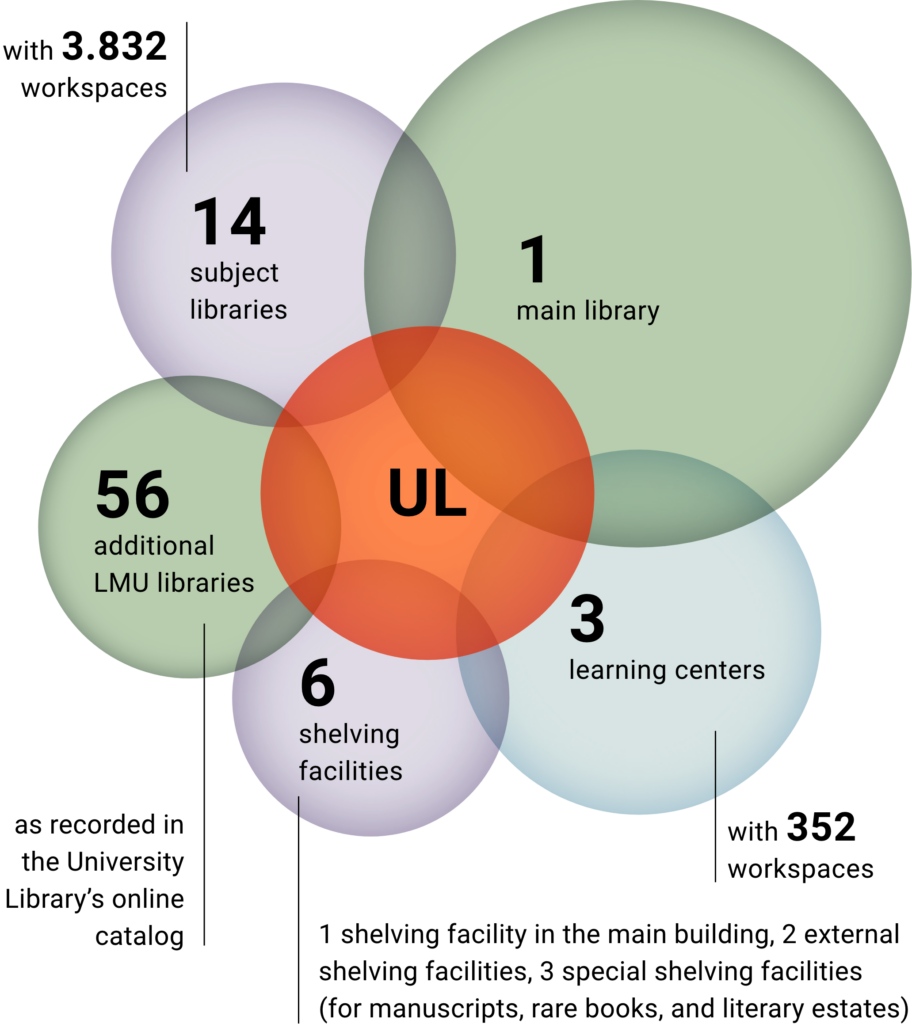

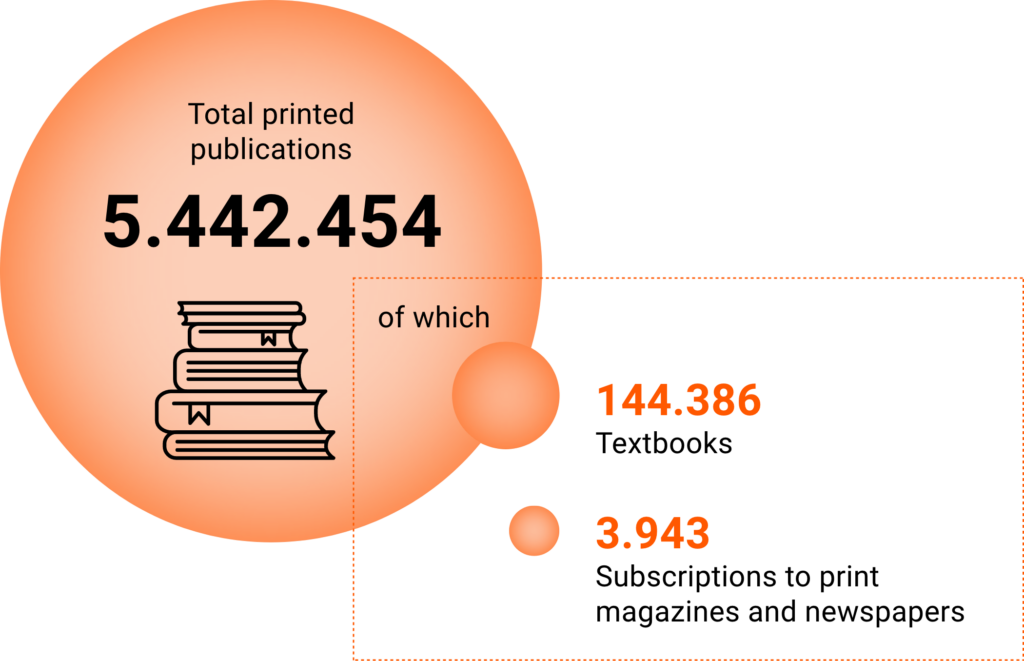

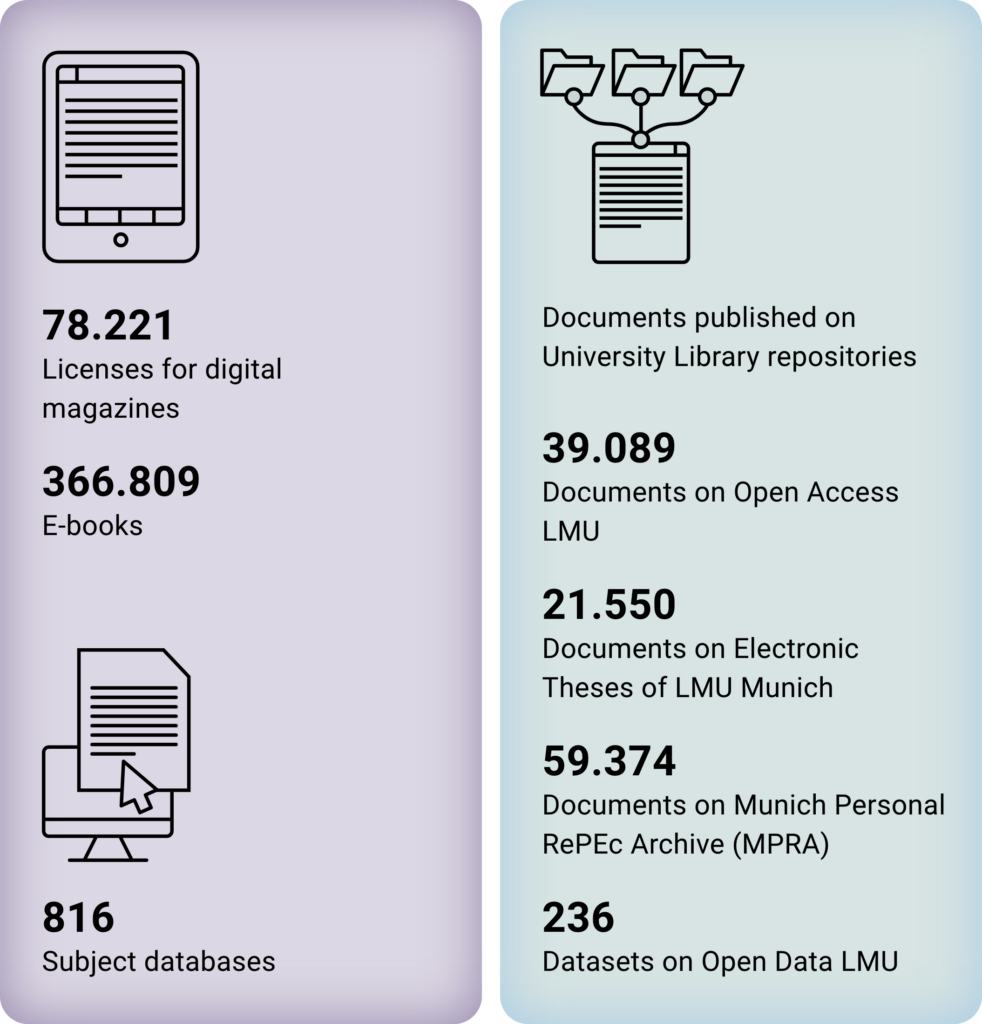

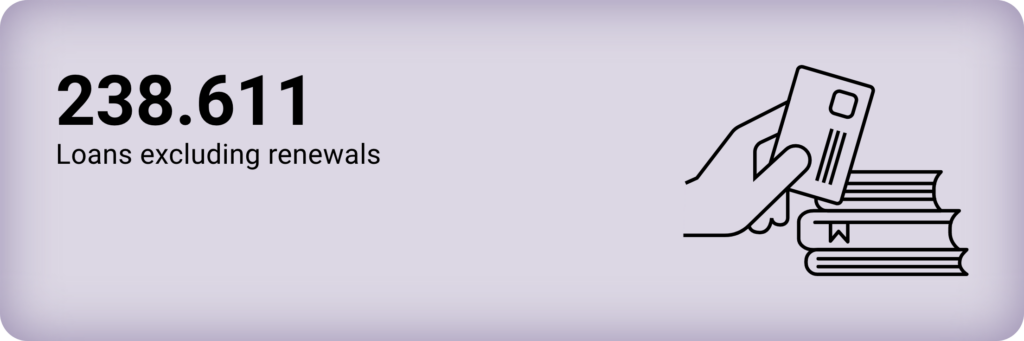

The University Library at a glance

The University Library includes:

The UL in figures

As per end of 2024

Library users and loans

The University Library has 202.155 registered users, including 76.720 students and 11.215 academic personnel.

As per end of 2023 | Graphic: Lisa Stanzel

Special Collections Department at the University Library